The renminbi in your pocket

Lessons from the dollar shortage of 1967 and the sterling devaluation

In a recent article in the FT on dollar balances at Chinese banks I observed the link to the fall of the renminbi against the dollar. There are echoes in this year’s renminbi performance with the devaluation of the pound against the dollar in November 1967. Just as with the renminbi in 2022, in 1967 a surprise war was the catalyst that brought on the devaluation. One very significant difference in the earlier example was the Bank of England had the ability to call on central bank swap lines to ease the pressure. No such mechanism exists in China, so the pain of dollar repatriation will be felt directly by the Chinese banks borrowers of dollars.

The devaluation from 2.80 pounds to the dollar to 2.40, a 14.3% adjustment, led to the famous comment from the Prime Minister Harold Wilson; “that doesn’t mean, of course, that the pound here in Britain, in your pocket or purse or in your bank, has been devalued.” No doubt Chinese officials will also claim that the ~10% devaluation of the renminbi against the dollar since April this year will have no impact on household finances. It is certainly having an effect on dollar balances.

The conventional explanation for the pound devaluation was the UK was beset by long-standing productivity problems, trade deficit and labour-relations problems and badly affected by the oil price rise of the Six-Day war in June 1967 between Israel and Arab countries that shut the Suez canal, disrupted trade and caused Arab countries to sell their sterling assets. The conventional view is neatly expressed in the opening paragraph of the Bank of England’s Annual report, shown above.

While these explanations are valid, none were new, except the Arab/Israeli war. Indeed, the Bank of England observed that conditions improved in early 1966 due to a “the slackening in demand for euro-dollars. At the same time, the outlook for the balance of payments seemed hopeful; and at home, resources were less strained and the standstill on prices and incomes was working well.1”

UK local authorities were significant borrowers of eurodollars. As the trade balance was in deficit, the only way to borrow was if someone else lent those dollars. In fact, despite the optimism of the BoE, UK conditions remained unattractive to foreign investors. As a consequence, the provision of dollars for local authority borrowers came from a forward sale of dollars by the Bank of England which in the summer of 1966, ‘sold dollars to a very substantial amount, well over several billion dollars2’ with New York banks being the counterpart.

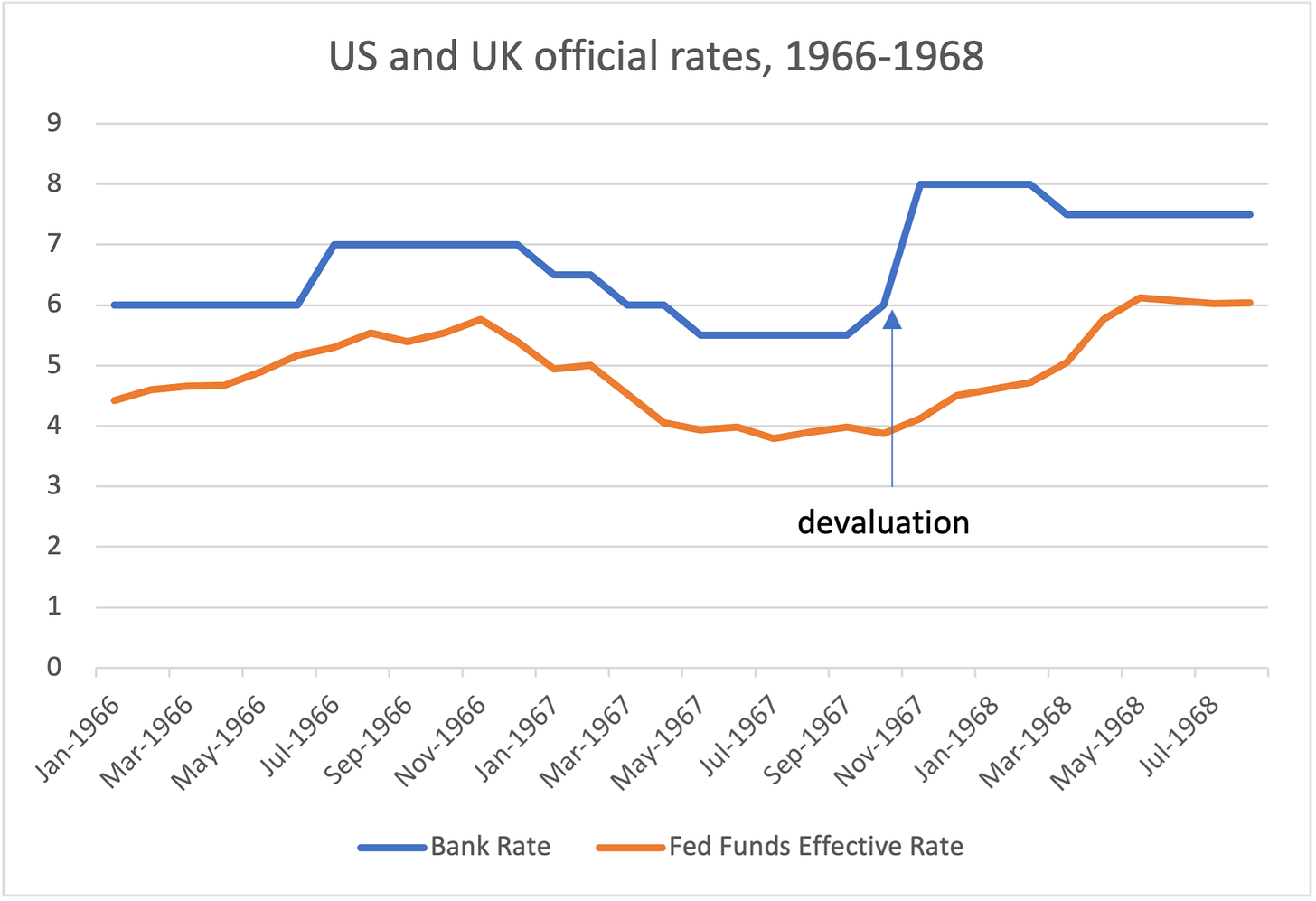

The relatively good times did not last. US interest rates rose through 1966, and liquidity conditions in US money markets encouraged repatriation of dollars. In June 1967, this demand for repatriation accelerated dramatically when the Six-Day war broke out.

Swap lines between the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve had been used regularly to smooth international liquidity conditions. As the Bank of England reported ‘from the second quarter of 1967 onwards, however, there was fresh recourse to such facilities, and in the second half of the year borrowing became very heavy. By the end of 1967 a net amount of $1,050 million had been drawn under the reciprocal swap facility with the Federal Reserve System and there were, in addition, substantial amounts outstanding under other facilities.3’

In short, the New York banks repatriation of dollars required the Bank of England to call on the Federal Reserve to create more dollars via the swap line to fulfil its obligations. The Federal Reserve eased monetary policy to satisfy the Bank of England’s demand for dollars. The Federal Reserve acted as an international lender of last resort to foreign central banks. In effect, the dominant international role of the dollar was confirmed.

The situation with the Chinese banks today is a little different. There will be no such creation of dollars by the Federal Reserve. Partly this is because the dollar balances concerned are on private sector banks. But this fact merely reflects an outsourcing of foreign reserve management by the Chinese authorities to commercial banks. The lack of a swap line between PBoC and Federal Reserve mean that no recourse to dollars will be forthcoming even if the PBoC wished to borrow to help its domestic banking system.

One can see this as a decline in dollar dominance as the Chinese banking system will have to learn to live without the Fed’s ‘lender of last resort’ facility. However, that may be a long-run destination. In the short run, the absence of Fed support means the Chinese monetary system has to take the strain on its own. In 1967 the pound sterling adjusted with a ~14% devaluation. In 2022 (and likely 2023) the renminbi has adjusted with a ~10% devaluation. Given the need for monetary easing in China, and the continued need for monetary tightening in the United States, a further devaluation of the renminbi is highly likely. The renminbi in your pocket is likely to be worth even less in future.

Bank of England Annual Report February 1967

Charles Kindleberger, An Economist’s View of the Eurodollar Market, 1970

Bank of England Annual Report February 1968

In the short run, the absence of Fed support means the Chinese monetary system has to take the strain on its own.

Inflation remains steady at 2.4%, so the strain has yet to show up there.

America's productive economy is half the size of China's, and slower growing.

Dynamic Covid Zero is paying off, with overwhelming support for keeping it and tweaking its implementation.

US-China trade has been falling steadily as China's use of currency swaps has been growing exponentially.