Crashing through barriers

Fixed income markets suggest regulators may have tested the financial system for the wrong stresses

(this article was originally published in the Financial Times Alphaville section on 5th May 2022)

In the original Jurassic Park film, Jeff Goldblum’s chaos theory mathematician has one of the film’s more arresting quotes: “Life will not be contained. Life breaks free, it expands to new territories, and crashes through barriers painfully, maybe even dangerously, but, uh, well, there it is.”

The financial universe is undergoing some painful barrier crashing of its own. Inflation is rampant for the first time in four decades. Stock and bond investors have lost money – some of them a lot of money. Foreigners who owe dollars are hurting. Yesterday, the Federal Reserve lifted interest rates by half a percentage point for the first time since 2000, and signalled signal that it will do the same at the next two meetings.

Yet, weirdly, there is actually little real sign of market stress.

Perhaps the reforms put in place after the global financial crisis of 2008 have really made the financial world a safer place? After all, nothing major broke as the Covid-19 pandemic closed the world’s economy. In fact, the regulators who pushed through the reforms were so pleased with how the system behaved in 2020 they’ve been crowing about it ever since1. But have we battened down all the right hatches? Will something break free?

Derivatives got a lot of regulatory attention in the wake of the financial crisis, with mandated moves towards central clearing to try to make things safer. Unlike most traditional asset investments, derivative markets require regular payments to mark positions to market prices through margins. Derivative margin is not a topic of many scary movies, but perhaps it'll pop up more often if markets continue their current rampage.

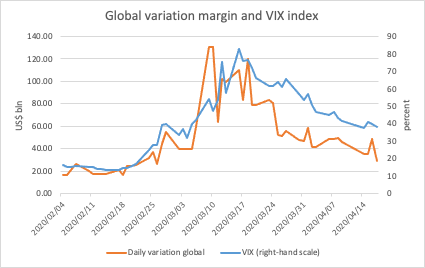

Changes in derivative margining is a good place to look for scares because margin is pro-cyclical; it rises during market disturbances and falls during good times. A clearing house or exchange will decide a riskier environment warrants more down-payment for every trade (initial margin). And more volatility automatically means more cash moving between users of derivatives (variation margin).

A rising level of variation margin is worrying because it is paid from free cash reserves or borrowed. As margin rises it may place an added liquidity demand on the entire financial system. In a stressed system, this will worsen tensions. During the 2020 coronavirus-triggered “dash-for-cash” it is estimated that combined margin demands increased globally by up to $500bn. No wonder the Fed and the ECB injected so much cash.

The VIX index reflects the expected US stock market turbulence, and was an uncannily accurate reflection of combined margin calls in derivatives in in the early stages of the pandemic.

Recent market moves have been notable for falls in both stock markets and a rise in bond yields across the curve. Basically, pretty much everything (except commodity prices) is having a bit of a tough time at the moment.

We do not have any current data but we can gauge increasing margin stress by the behaviour of market instruments such as the VIX volatility index. The has risen but is hardly showing signs of a freak-out. But the implied volatility of fixed income markets has shot higher, as yields rise and bond prices plummet.

The cost of insuring against higher yields is now the highest since early 2011. And it is in fixed income markets, rather than equity markets, that we should expect the greatest margin stress as fixed income markets have suffered some of their biggest losses in decades.

The Fed and the European Banking Authority tests to stress their financial systems have come to assume a familiar pattern: a crisis means stock prices fall, the dollar rises against other currencies, interest rates collapse and the yield curve steepens. That’s not the configuration we’ve got now; stocks are down (tick), the dollar is up (tick) but interest rates are rising a lot everywhere, and the yield curve has flattened.

It could be that regulators have become so used to looking for stress in equity markets they are not prepared for current conditions. This time maybe we should be looking at measures of fixed income volatility, not stock volatility for an accurate measure of stress in the system.

Yesterday the Fed announced the start of quantitative tightening – trimming its $9tn portfolio of bonds by $47.5bn a month to begin with, soon to rise to $95bn- as well as lifting interest rates by 50 basis points, the first half-point hike since 2000. This official tightening of monetary conditions is being accompanied by tighter financial conditions through margin. It will be interesting to see how the combination interacts.

A rise in bond yields does not figure in stress tests on either side of the Atlantic, but variation margin is almost certainly rising in fixed income markets. Perhaps the level of implied volatility in swaptions may be a good way to see how financial life is really evolving.

https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d526.pdf