While the UK media fills with pained stories of UK mortgage woe, spare a thought for the other side of the coin; the lenders. No, not the banks. In the ugly acronym of international regulators it may be the NBFIs (Non-Bank Financial Intermediaries) we need to watch. These unregulated lenders are prone to liquidity shocks and capital weakness. Plus, their efforts to avoid liquidity (and solvency) issues mean they pull back lending abruptly - with wider economic implications. In fact, they are already doing so. But don’t expect the media to cover the NBFIs till there is an actual crisis.

First, the good news. In the reassuring words of the Bank of England following the bankruptcy of Silicon Valley Bank,

“The UK banking system maintains robust capital and strong liquidity positions. It is well regulated – in line with standards implemented by UK authorities that are at least as great as those required by international baseline standards – and subject to robust supervision. The sector’s profitability is strong, having improved as interest rates have increased, and it is well placed to continue supporting the economy in a wide range of economic scenarios, including in a period of higher interest rates.”

At the end of this month (June) the results of the Bank of England’s bank stress tests, will be ready for the forthcoming Financial Stability Report. Known as the ‘Annual Cyclical Scenario’ (ACS), the last version was performed in 2019. Results from the 2019 ACS showed that even under stressed scenario, UK banks remained well above the hurdle point signifying concern about capital.

Since then, banks have been subject to the real-life stress of the COVID19 ‘Dash For Cash’, and the accompanying deluge of fiscal aid and central bank liquidity now washing through the system in the form of inflation which has brought about the current ‘mortgage misery’ of much higher rates - though not as high as inflation. So, the wheel of financial policy turns; action begets reaction. But at least we seem unlikely to repeat the last financial debacle.

The starting point for the 2019 ACS was 14.5% CET1 risk weighted capital. The level of CET1 at end-2022 was reported to be 14.3%, though adjusting for changes in regulatory definitions, it is actually slightly higher than the starting point of the 2019 ACS. So far, so good for banks.

And the stress scenario is VERY stressful.

And a delve into the ACS assumptions on market volatility for equities, rates and currencies is frankly eye-watering!

So, in theory, we don’t have to worry about the UK banking system and can reserve our concerns for the unfortunate borrowers.

But, as we discovered in the LDI episode of September 2022, it may not be banking capital we need to worry about, but liquidity and capital risk in the non-banking financial sector. As the IMF noted in a 2022 paper on UK financial system resilience: “

Capital requirements under Basel III made lending in certain segments unattractive to banks. On the contrary, non-banks were unaffected by Basel capital requirements and provisioning rules for banks, and thus were able to fill the gap. Motivated by higher yield, non-banks served borrowers shunned by banks.

There is no stress test for NBFIs. And the regulatory reforms post-GFC have encouraged NBFIs.

Overall UK credit conditions are affected by any pullback by this unregulated sector. Indeed, since mid-2021, as inflation rose and steep rises in interest rates became inevitable, lending by NBFIs declined sharply as a percent of GDP, from ~80% of GDP to 66%, and stands at the lowest point since 2004.

This has two effects. First any capital (and funding) stress from Bank of England rate rises is likely to manifest itself in NBFIs before banks. Secondly, NBFIs are incentivised by concern for survival to pull back lending further.

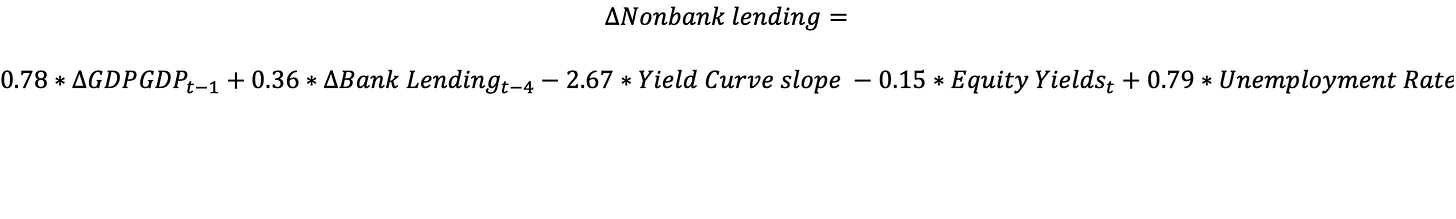

The same IMF paper contains a model for drivers of NBFI behaviour:

There is some comfort in the IMF formula. The strongly inverse relation to the yield curve suggests NBFIs will find current steeply inverted curve an attractive lending proposition. But that pre-supposes their own cost of funding remains manageable and their outlook on the wider economy remains optimistic. Both look much less optimistic than they did.

So, we have two channels of concern for UK financial conditions: the condition of borrowers dependent on NBFIs and the condition of the NBFIs themselves.

Oh, this isn’t a specifically UK story.