The Cost of Public Service

Central bank losses don't mean QE was a colossal waste of resources, it just looks that way.

Apropos of nothing, here’s a frivolous and piecemeal look at how central banks across the developed world are dealing with losses. Reports of central bank losses threatens to be such a common saga across the developed world that detail becomes tiring (all those noughts). Instead, here are a few current tidbits to place next to the overview of European central banks accounts from early June.

Some time ago, I suggested losses at the Swiss National Bank in 2022 may reach CHF120 bln, or 15% of Swiss GDP. In fact, declared losses for 2022 reached CHF 131.5 bln, or 18% of Swiss GDP. The SNB retains the dubious accolade of ‘biggest QE losses as a percentage of GDP in the developed world.”

Having taken its lumps last year things are beginning to look relatively better for the SNB - though partly because things now look considerably worse for other central banks.

Based on a moderate amount of guesswork, the SNB’s portfolio performance in the first six months of 2023 may deliver a small profit of ~CHF5 billion, about half the earnings levels reported for 2020 and 2021 on an annualised basis (before last year’s colossal drawdown). In short; a rebound in equity values offsets continued losses from bond investments and rising cost of interest on domestic reserves.

This happy pattern does not translate to the income statements of central banks elsewhere; most other central banks have no equity portfolio to offset the bond and interest losses. On the other hand, the relatively better shape of the SNB is highly dependent on the vagaries of equity markets.

One interesting nugget from the SNB’s 13F submission is the portfolio recently added Northrup Grumman and L3Harris Technologies to its largest 200 US equity holdings. Both are defence stocks and Northrop Grumman has been a member of the S&P500 for decades so its previous absence from the SNB portfolio seems a curious omission, now rectified. Is the inclusion of defence stocks in the SNB portfolio another example of the geopolitical reset caused by the Ukraine war? Perhaps the Northrop Grumman omission was simply an oversight.

At least the SNB have significant reserves to call upon. The loss last year was met by a transfer of CHF 142 billion from reserve fund. Other central banks have to find other ways to make good their losses.

For instance, the Bank of England expects to receive transfers from the UK Treasury for QE losses under an indemnity arrangement dating back to the GFC. Relatively recent estimates by the BoE suggest transfers will amount to about GBP 30 billion pounds a year in 2023, 2024 and 2025 and then about GBP 20 billion per year for 2026, 2027 and 2028. It received its first tranche of GBP11 billion in October last year, then another GBP3 billion in January.

The BoE made a profit of nearly GBP 4 billion from its ‘financial stability’ intervention in October last year which is welcome break from the expected stream of losses. Unfortunately, short-term market interest rates have risen 200bps from when those estimates were recorded at the end of March 2023, meaning losses will exceed current BoE projections unless rates retreat. Later this month (25th July) we’ll get an updated ‘Asset Purchase Facility Quarterly Report’ which may (not guaranteed) shed some more light on how much money the BoE thinks it will lose in the next few years. We can’t wait.

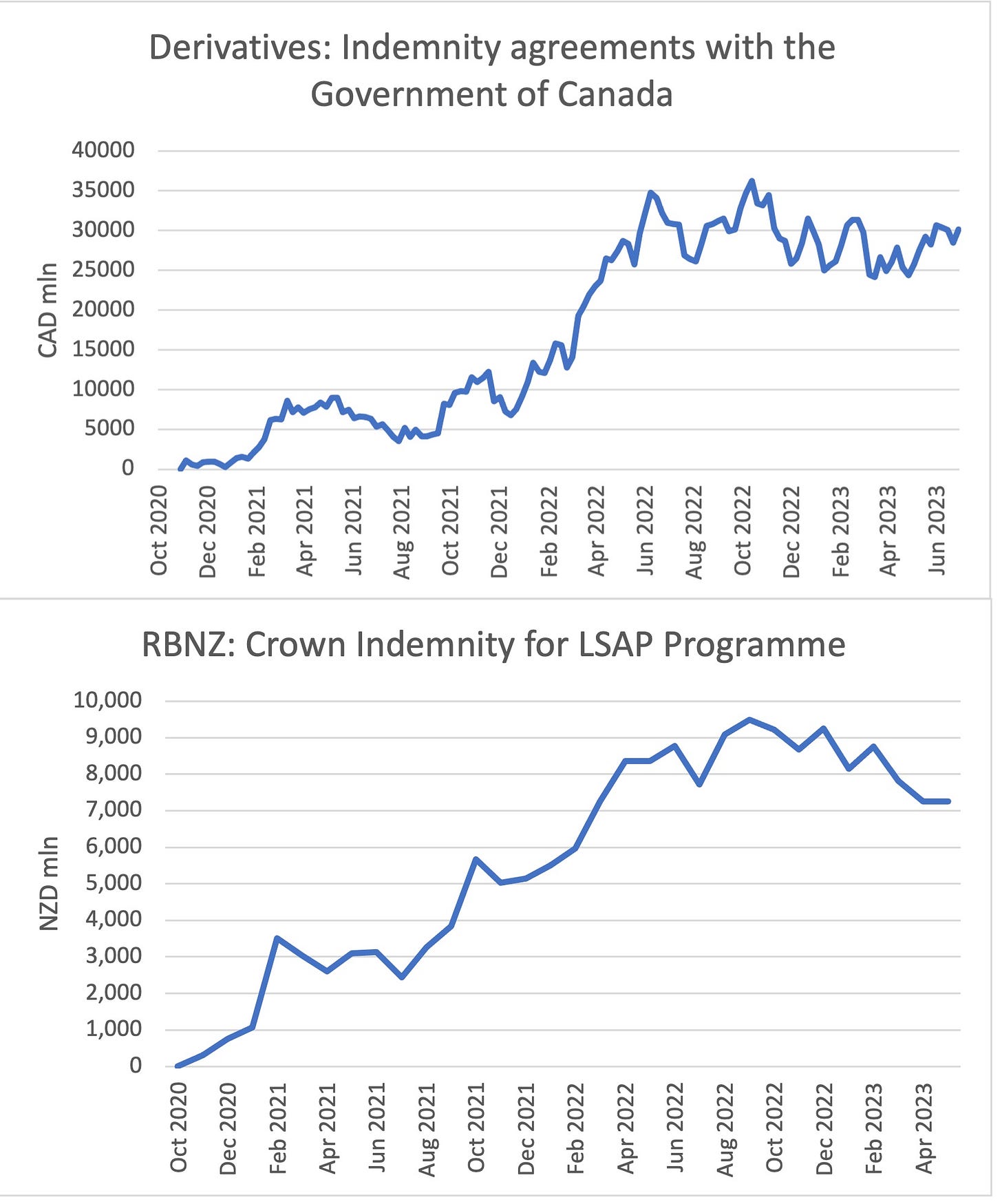

Other central banks are handling losses with a much greater aplomb. Both the RBNZ and the BoC have ‘indemnity agreements’ with their respective governments similar to the Bank of England. Unlike the BoE, however, there is no obvious transfer of cash from the fiscal authority. Instead an asset is entered on the central bank balance sheet as a ‘derivative’ on government funding - which as long as the loss is temporary, need never be paid and is amortised gradually through seigniorage. So far, the approach seems to be working well. Both RBNZ and BoC have seen a stabilisation in the ‘indemnity derivative’ facing the government and may well be past the worst.

The Fed adopts a different approach; currently booking a loss ‘deferred asset’ at US$76 billion. This already exceeds the central case peak loss estimated previously by the Fed at US$58 billion, a loss, by the way, expected to peak at the end of 2024, not the middle of 2023. At the current run rate, the ‘deferred asset’ will exceed USD150 which equates to one standard deviation error above Fed central case estimates. That has implications for US fiscal policy which will miss out on remittances from the Fed for several years, possibly till 2027.

So far, political economy repercussions seem remarkably restrained in the US, perhaps because both major parties acceded to the short-term fiscal benefits of QE.

The luxury of compromised politics doesn’t apply in Germany where the Bundesbank faces a growing stream of criticism. That’s normal. The Bundesbank faces domestic criticism for just about every decision that is made at the ECB though criticism is getting more pointed. The Buba has had to deny that its own QE losses will require a recapitalisation by Berlin.

That claim may turn out to be premature. With rates continuing to rise and bond prices falling, QE losses will continue to weigh heavily on the Bundesbank, as with most European central banks. The fiscal implications of higher funding costs and central bank losses have yet to be fully felt and may be uncomfortable, especially for fiscally challenged countries.