Adam Tooze makes interesting points in his latest piece (link below). The relationship between dollar/commodity price and global growth is definitely worth considering.

I want to raise a few points.

Adam is right to point to trade as an essential original contributor to dollar dominance - especially extra-US oil trade. But it wasn’t the only contributor, and anyway an origin story doesn’t have to define the current state of affairs.

This is not an oil tanker

Once sufficient dollars had escaped from the US via trade, capital allocation became as important as trade flows in the dollar financial system. This change was itself advanced by the Oil Shocks - with a clear change in operating procedures from the mid-1980s onwards, which became increasingly focussed on allocation. Was the investment by the Public Investment Fund (PIF) in Disney, Uber, Facebook, Starbucks, Pfizer and Newcastle United football club made with direct reference to current Saudi Arabian oil trade profits? Not really. It’s purpose is to manage $620 billion of wealth inside and outside Saudi Arabia accumulated from the past sale of oil, not the current trade in oil. It’s job is to convert past shipments of oil into entries on an digital ledger, often in the United States. Those digital entries are a good part of Saudi wealth.

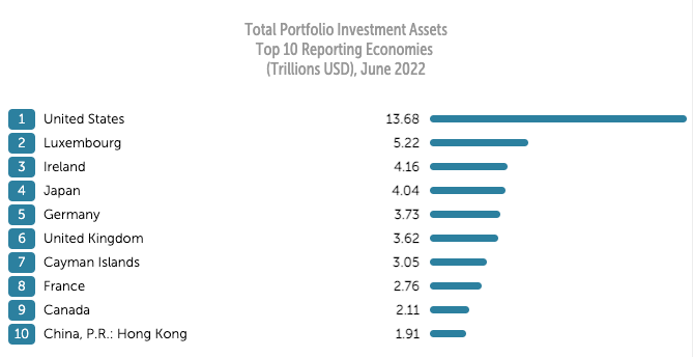

Capital flows represent the change in ownership of assets. They are the management of accumulated wealth, which include, but are not limited to, current trade flows. Currency denomination is extremely important to owners of wealth. Who buys goods made in China? Everyone. Who, of sound mind, willingly converts the denomination of their portfolio into Chinese yuan or Brazilian real? The answer is left hanging.

Trade flows may switch to regional currency but, in general, a significant portion of profits eventually end up managed by asset managers in the US or a US proxy (Europe, Singapore, Dubai) denominated in dollars or dollar proxies - perhaps in football club ownership.

It is not just commodities. This trade/wealth nexus has pressing relevance for the Apple/Foxconn relationship. The important article by my friend Jay Newman in yesterday’s FT highlights the dilemma facing Apple (existing wealth generators) versus wealth management. Where has the value accrued? Mostly it has accrued to the Apple shareholders, denominated in dollars. Who are the Apple shareholders? They are global investors, as well as Americans, who are happy to hold their assets in dollars.

How can Apple continue to succeed when it seems deeply allied to a repressive, anti-Western China? The adaptation may be brutal, and Apple may not succeed, meaning some of the wealth gained by the relationship will erode. Just as likely, Apple itself will deliver more products in the rest of the world to offset its loss of Chinese market and manufacturing. Or its role will be apportioned to another, more amenable company providing a similar service, mostly likely with shares denominated in dollars.

At what cost in terms of growth and portfolio value will the West transfer its energy and technological requirements to friendly hands? Certainly, it will be bad for some growth (perhaps the growth of Apple). How it will translate into wider sphere is an open question. There have been short periods when falling global trade made little difference to GDP; 2016-2019 for instance. Trends in trade growth are generally more aligned to industrial growth trend than growth in services. The United States has a smaller trade sector than China and a smaller industrial sector, both as a percentage of GDP. As often occurs in rivalry, an important consideration is who suffers most.

Some TSMC leaders express scepticism about US ability to build advanced semi-conductor capability using government incentives, yet seem to have forgotten their own capability was founded on government subsidies. Give it 5 years and they may be convinced.

It is by no means clear trade will shrink. As China asserts a clear political schism with the West, its trade surplus has risen to its highest level, meaning it is importing dollars (or dollar proxies) at the highest rate ever and will need to recycle them. Just as the Middle Eastern oil producers unleashed the Eurodollar market, somehow those earned dollars need to be invested. After the invasion of Ukraine and the imposition of sanctions on Russia, Chinese banks ran down their dollar balances (deposits and loans), but their dollar portfolio claims continued to rise. That dollar stuff has to go somewhere.

As a final comment, I listened to a crypto liquidity provider recently explain that a mainstay of his business is to extricate wealth from China into dollars, within the letter (though probably not the spirit) of Chinese law. The flow is not two-way.