Foreign Explosion, Few Americans Injured

The real lesson of the disruption in the UK financial market is the long reach of the Fed

In response to what some have called ‘not quite a Lehman moment… but close’, the Bank of England has been forced to begin buying long-dated government bonds while simultaneously engaged in a monetary tightening cycle. For those with a particular type of humour, this looks remarkably similar to the ECB plan to buy the bonds of ‘fragile’ Eurozone countries, while it tightens rates in response to inflation.

Of course, this week’s excitement is nothing like a ‘Lehman moment’. Such comments reveal a common self-centred regard that UK financiers have for their own patch. Problems in the Gilt market have some global consequence, but not much. Particularly as UK authorities control both fiscal and (indirectly) monetary policy. What they don’t control is the currency. It is the currency on which we should be focussed.

For the episode reveals the hidden costs of QE for countries that are not THE global reserve currency. The Japanese Yen has undergone similar trouble. I have no doubt the Euro (or constituent member states within it) will undergo further ‘rapid and uncomfortable adjustment’ in response to the US exercise of its ‘exorbitant privilege’.

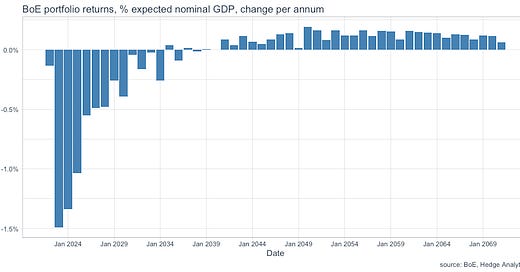

Meanwhile, drowned by the excitement in UK financial markets caused by current Fed policy, the costs for the Bank of England of emulation of past Fed policy mounting. Let’s look at one nasty aspect of tighter interest rate policy.

UK SONIA forwards suggest rates rising to ~6% by Q3 2023, then dropping back to around 4.5% over the ensuing 3 years. At those levels of rates, the revenue streams associated with the BoE Asset Purchase Facility (APF), and the reserves that fund that portfolio are deeply negative. Losses that accrue to the APF are indemnified by the Treasury. In practice this means rising interest rates (monetary policy) translates directly to fiscal policy (a higher cost to government). Mr Darling, and later Mr Osborne, signatories of the indemnity must be glad not to have to face up to the consequences of a promise made over a decade ago. ‘ExorbitantPrivilege’ discussed this previously, back in mid-June (see ‘No Great Expectations’).

Under current market pricing (see above), the costs are very significant indeed - a hit to the government of 1.5% of GDP in 2023, and a series of large costs every year till the end of the decade.

Now we hear whispered words that 'economic advisors' to the new Prime Minister are advising 'tiering' of interest rates paid to banks on reserves as a means of addressing such losses.

The word 'tiering' has a nice gloss of professionalism. But that gloss can't disguise the fact that fiddling with how interest rates on reserves are paid probably just converts one problem into another.

The reason interest is paid on reserves is not because the BoE wants to be nice to banks. The interest rate paid has the practical effect of establishing a floor in market interest rates that is controlled by the central bank. If that interest is adjusted to save money for the Treasury, the ability of the central bank to control interest rates may be compromised. That’s hardly a good outcome for any central bank that uses interest rates as its primary policy tool. It is particularly risky in an inflationary environment. Ultimately this will be reflected in the value of the currency - and it is not bullish.

What about the other suggestion of transforming reserves into bonds? That would remove the funding risk in the QE portfolio, but would force banks to take interest rate risk they otherwise would not want. In response, banks either shed other interest rate risk to get back to equilibrium (perhaps by selling Gilts), or reduce other assets, such as loans. Hardly the outcome needed for an economy facing recession. And not the outcome desired by the new government.

No easy way out. In these circumstances it is usually better take the lumps and follow existing agreements, whatever the cost. Monetary extend and pretend can only work while the economic hegemon (the Fed) is playing the same game. How long will this turmoil continue? As long as the Fed continues to tighten. What will cause a change? If history is a guide, the only thing likely to affect Fed policy is significant financial or economic disruption in the United States itself. And we have not seen anything like ‘significant disruption’ yet.

Ray Dalio: “Mechanistically, the UK government is operating like the government of an emerging country, producing too much debt in a currency for which there is not much world demand".